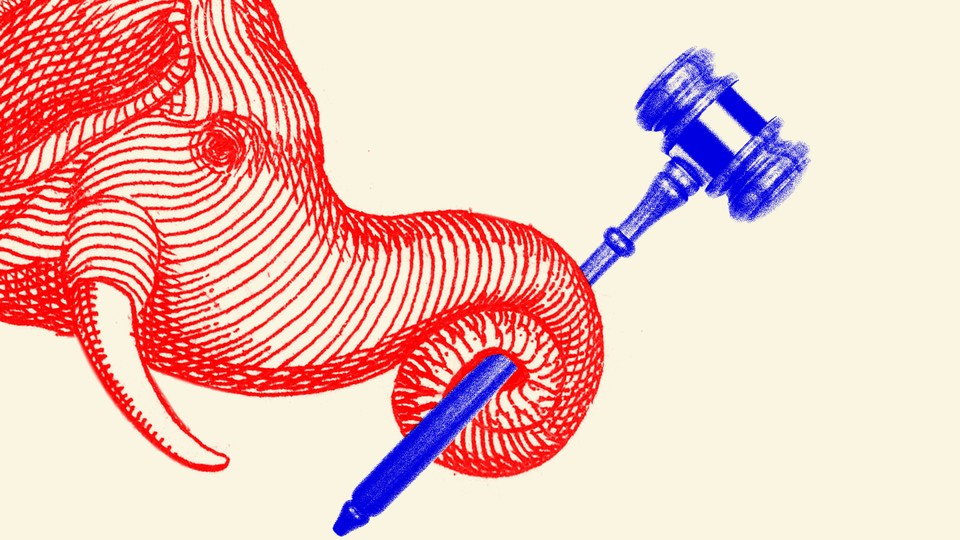

Republicans Are Grabbing Power Because SCOTUS Said Go for It

In North Carolina, GOP lawmakers are redrawing maps that are neither unconstitutional nor illegal—yet skew heavily in their favor.

Updated at 12:04 p.m. ET on November 7, 2021

This week, Republicans in the North Carolina General Assembly approved new maps for electing state legislators and U.S. representatives. The results are what you’d expect for a red state: Of the 14 U.S. House districts, including a new seat added after the latest census, Republicans can expect to win nine, 10, or perhaps 11; they can also expect strong and possibly veto-proof majorities in the state legislature.

The problem is that North Carolina isn’t really a red state. Its electorate is roughly evenly split. In 2020, Donald Trump edged Joe Biden by 1.3 percentage points, but more than half of the state’s votes for U.S. House seats went to Democratic candidates—yet Republicans still won eight of 13 races. The state has a Democratic governor.

North Carolina Republicans are doing this because it increases their power, and because they can. They control the legislature, which draws the maps, and state law says the governor cannot veto the maps. Besides, they have reason to believe no court will stop them, given the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision washing its hands of concerns about partisan gerrymanders. Although Chief Justice John Roberts acknowledged that highly distorted maps—like this new one from North Carolina—are “incompatible with democratic principles,” he also said the high court had no standing to interfere.

In a now-infamous statement in 2016, one North Carolina Republican state representative, David Lewis, noted, “I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats, because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.” The legislature was then drawing new maps because its initial post-2010-census maps had been thrown out as an unconstitutional gerrymander.

As Lewis wrote with Senator Ralph Hise in The Atlantic, the remark was not a Kinsley gaffe but an affirmation that the maps were designed for partisan advantage and not to discriminate racially. “You don’t need to agree with the statement, and you don’t need to support partisan considerations in redistricting,” the pair wrote. They were just explaining, for the benefit of federal judges and anyone else who was listening, what they were about to do. Now, with the Supreme Court’s tacit permission, the Republicans are doing it again.

Most states redistrict every 10 years, after new census data become available. But in North Carolina, redistricting has become a constant hobby, alongside drinking craft beer, making fun of Charlotte, and griping about Ted Valentine. In 2010, Republicans took control of both chambers of the legislature for the first time since 1870. They promptly got to work, including drawing new maps after the 2010 census, as well as passing bills to make voting harder. Those maps were repeatedly and successfully challenged in state and federal courts for being unconstitutional.

The legislative maps that elected the current general assembly are constitutional—at least no court has said otherwise—but they are deeply gerrymandered, skewing the results toward Republicans in a more or less evenly divided state. In 2020, the GOP won a tiny majority of the votes for state House (49.99 percent to 49.06) but took 69 seats to Democrats’ 51. On the Senate side, they won the aggregate popular vote 50.8 percent to 47.9, and won 28 of 50 seats.

After the U.S. House maps were tossed in 2016 as unconstitutional racial gerrymanders, Republicans designed new ones that relied on solely partisan data, not race (though there’s a strong correlation between Black and Democratic voters in North Carolina). Progressive groups challenged those, too, taking them all the way to the Supreme Court, which had previously shied away from ruling against partisan gerrymanders. A certain amount of politicization was inevitable, the Court had previously concluded; who were they to say what was too much?

The plaintiffs brought elaborate new mathematical measures to demonstrate the egregiousness of the North Carolina maps, as well as Democrat-drawn ones in Maryland, but Roberts’s majority opinion slammed the door shut on federal-court action against partisan gerrymanders, saying it was a matter for state courts or Congress. (Democrats in Congress have since tried to pass legislation addressing the problem but have been blocked by Senate Republicans.)

Ahead of the new round of map-drawing, looking for a better PR strategy, North Carolina Republicans announced that they would use neither racial nor political data to draw the new maps. Nonetheless, the maps the GOP majority adopted seem precisely designed to squeeze the maximum Republican advantage.

“This gerrymander is more than just an effective gerrymander. It’s an extremely efficient one,” Asher Hildebrand, a public-policy professor at Duke University and a former Democratic congressional staffer, told me. (I am an adjunct journalism professor at Duke’s public-policy school.)

Republican map-drawers may not have had access to partisan data, but they probably didn’t need them in order to draw such ruthlessly efficient maps: As successful politicians, they likely know their districts down to the precinct level, even without referring to other data. Beyond that, they have a decade of experience tussling over the districts from which to work.

Republicans have attributed the lean of their maps to the state’s existing partisan geography: Democrats are highly concentrated in cities such as Raleigh, Greensboro, Charlotte, and Durham, while Republicans are spread elsewhere. They have a point, to a point. Democrats’ clustering in urban areas is a growing problem for the party. But outside groups and Democrats also produced proposed maps that would have been more evenly balanced, or less tilted toward Republicans.

I live in North Carolina, and I’ve sensed something of a nonchalance about the map-drawing process this fall. Maybe that’s because of gerrymandering fatigue, and maybe it’s because everyone expected Republicans to draw maps that created as many GOP safe seats as possible, but everyone has also always known the matter would end up in court. The legislature’s maps are just an appetizer.

Plaintiffs including the NAACP and the voting-rights group Common Cause filed suit last week, even before the maps had been adopted. The Democratic election super-lawyer Marc Elias filed another case Friday afternoon. “I hear it is perfect weather to be in court in North Carolina right now,” Elias tweeted this week. (Republicans say these suits are about gaining partisan advantage, just like their own maps.)

But judges may not be as helpful to Democrats in the 2020s as they were in the 2010s. The U.S. Supreme Court decision on partisan gerrymandering rules out one avenue. Cases that center on race are getting harder too: The Court has continued to weaken the Voting Rights Act, and plaintiffs may approach new cases with trepidation, fearful that the more conservative Court could go further. That leaves state courts, but those might be less favorable now too. A Republican now leads the state supreme court, and although Democrats retain a 4–3 edge, they may lose it in 2022.

This makes for a bleak landscape. Any scheme that takes a roughly 50–50 population and produces a result as skewed as 10–4 or 11–3 in House seats can hardly be called fair or democratic, as Roberts acknowledged. Yet that doesn’t mean the arrangement is unconstitutional or illegal. With the courts walking away, the only remedy is for proponents of a fairer system to win legislatures and Congress and change the laws—a task that slanted maps make harder, if not impossible, to achieve.

This article originally stated that Republicans won 10 of 13 races in North Carolina in 2020 elections.